[Note to the Reader — Given the growing praise of Carl R. Trueman’s book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self as a book that can help shed light on our current culture as regards LGBTQIA+ thinking, I have decided to make my examination of the book free to all. I am trying to be as painstakingly precise in my critique of his book, so that readers will understand why it is a dangerous book that perpetuates, rather than opposes, the kind of thinking that has gotten Western culture into the mess it is currently in — namely, collectivism and constructivism.

Substantial, researched writing is something that takes time and effort. It really is a second job of sorts for a lay researcher/writer like me. So I ask that you consider funding my efforts by becoming a paid subscriber or giving Logia a donation. These buttons will be interspersed throughout the articles sparingly. Thank you. — Hiram R. Diaz III]

[Continued from Pt.1]

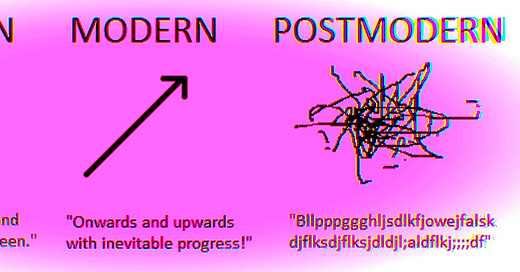

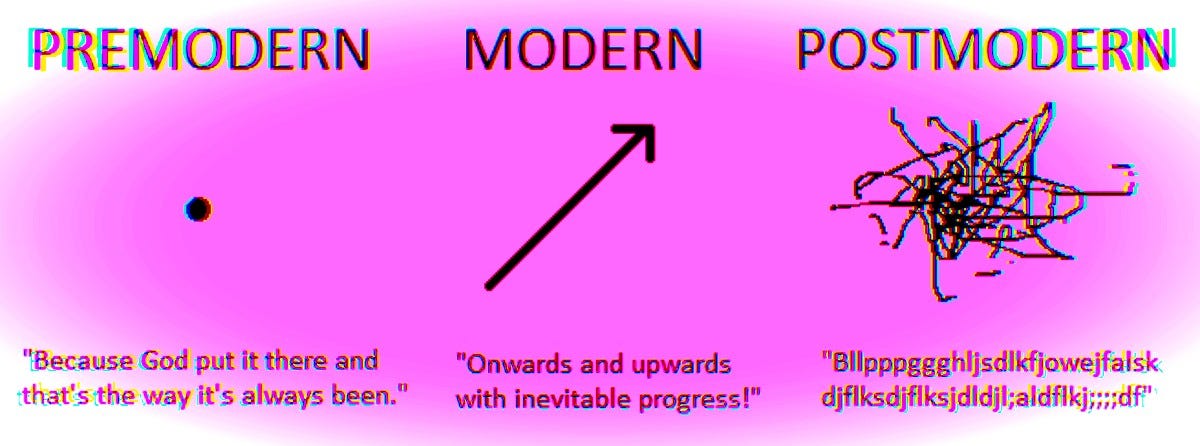

§II. Postmodernism or “Late Stage Capitalism”/Late Consumerism/Modernism?

We have already seen that Trueman’s depiction of the contemporary self is nearly identical to the standard academic depiction of the modernist self. But what we have not seen, and what one does not find in RTMS, is Trueman dealing with the postmodern understanding of the self. In fact, we do not find him addressing postmodernism in RTMS at all in a substantial manner. Given that the self is a particularly strong focus of postmodern philosophy, this creates a gaping hole in his genealogical project.

The entire book only mentions postmodernism three times. The first mention is made by Rod Dreher who seems to identify the present era as postmodern.1 The second mention is also made by Dreher, who seems to identify modernity and postmodernity as the same thing, although his meaning is somewhat ambiguous.2 The final mention of postmodernism is made by Trueman, and he also does not clarify what he means by the term.3 In order to understand why Trueman excludes a discussion of the postmodern self, as well as why he does not clearly explain what he is speaking about when he use the term, we must look at the larger corpus of Trueman’s writing.

When we look at his writings elsewhere, we see that Trueman does talk about postmodernism with a little more clarity. The problem is, however, that he has done so in a manner that is contrary to basic scholarship on the subject. For instance, in an article for Reformation 21 titled “Stating the Obvious,”4 Trueman takes issue with evangelicals whom he believes are repeating false generalizations about postmodernism in order to make money. Among the generalizations he finds problematic, he includes their statements concerning postmodernism’s —

Rejection of “the optimistic belief in human reason and progress that characterized modernity”

Crisis in confidence in science

Privileging of stories/narratives over and against propositions

What is noteworthy about this is that by problematizing the common academic understanding of modernism, Trueman makes it possible to deny that its successor (viz. postmodernism) can be characterized by the above listed characteristics.

The glaring problem here, however, is that what Trueman says are false generalizations are, in fact, textbook descriptions of postmodernism. In his book Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction, philosopher Christopher Butler writes —

A great deal of postmodernist theory depends on the maintenance of a sceptical attitude: and here the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard’s contribution is essential. He argued in his [book The Postmodern Condition] (published in French in 1979, in English in 1984) that we now live in an era in which legitimizing ‘master narratives’ are in crisis and in decline. These narratives are contained in or implied by major philosophies, such as Kantianism, Hegelianism, and Marxism, which argue that history is progressive, that knowledge can liberate us, and that all knowledge has a secret unity. The two main narratives Lyotard is attacking are those of the progressive emancipation of humanity – from Christian redemption to Marxist Utopia – and that of the triumph of science.5

In this one paragraph, Butler states that postmodernism is marked by its

Rejection of “the optimistic belief in human reason and progress that characterized modernity”

Acknowledgement of a crisis in confidence in science

Rejection of “metanarratives”6

Trueman’s evangelical colleagues were not regurgitating false generalizations; they were accurately describing postmodernism in a manner consistent with scholarly descriptions of it. Why, then, does Trueman claim that the above characteristics are not properly attributable to modernism and, what is more, that postmodernism is falsely characterized as opposing those characteristics?

He gives two reasons. The first of these is that postmodernism and its influence on society and academia is overblown. Proponents of postmodern theories may claim that the “postmodern turn” is responsible for upending the traditions, institutions, and core beliefs of Western civilization, and that it is a movement, therefore, of epochal significance — but the grandiose claim is not unique to postmodern thinkers. In his 2008 Westminster Seminary inaugural lecture, Trueman states —

Postmoderns tells us that because of this radically relativizing insight [i.e. the insight that “the whole idea of grand narratives,” and therefore of historical grand-narratives as well, “and of the accessibility of truth in any traditional sense” has been shown to be utterly implausible] we therefore live in an age of epochal change, where everything once certain is now exposed as negotiable and volatile and that a fundamental cultural paradigm shift has occurred.

As a historian, of course, I am never impressed by claims about epochal

events and paradigm shifts. I am too well aware that every age has made claims

to being epochal…human beings have consistently and continuously engaged in the creative struggle to transform culture and to leave their mark on the world around them. This surely indicates something about the amazing and awesome human drive to make a difference, to make my name and my age the decisive one. Is the postmodern turn of epochal significance? Only time will really tell, but if I were a betting man, I would wager heavily against it being so. 7

Trueman’s reason for undermining the significance of postmodernism is that he, as a historian, is all too familiar with claims that one’s era is of epochal significance. The truth of that kind of a claim, in other words, can only be determined after the fact.

Yet while Trueman is right to say that he would be betting on a future that cannot be foreseen with 100 percent accuracy, his article was written in 2005 at least two decades after postmodernism was already having a significant influence on Western intellectuals and artists. As we noted already, by the 1980s postmodernists were already striking at the very root of the modernist period’s founding cultural and philosophical beliefs, demonstrating that Trueman’s uncertainty — in 2005 — about its historical significance was, at best, unfounded. But what is more, even if his uncertainty was not completely unfounded in 2005, a simple perusal of the fragmentation of the West in the year 2022 demonstrates in no uncertain terms that postmodernism’s influence is one which we are still feeling today.8 If RTMS is supposed to be giving readers in 2021 a genealogy of how we intellectually and culturally got to where we are, its failure to touch on postmodern ideas regarding the self is inexcusable.

The “historian’s excuse” noted above is not the only reason he gives in his Westminster inaugural address. Continuing in his address, he states that —

…at a more sophisticated level…my skepticism about postmodernism is rooted in my attraction to the arguments of critical [Marxist] theorists like Frederic Jameson, Perry Anderson, and Terry Eagleton.9

Trueman gives us a more substantial reason for his uncertainty. It is based upon his acceptance of the Marxist interpretation of postmodernism as form of “late stage capitalism.” which he, for the sake of avoiding being misidentified as a Marxist, calls “late consumerism.”10 According to this Marxist interpretation, capitalism’s corrosive effect on society is most clearly manifested in the commodification11 of traditional values, practices, and social and religious institutions. And as for commodification, it is the fruit of Western civilizations foregrounding of the individual — i.e. the modernist self.

For Trueman and the abovementioned Marxists, postmodernism “with all of its vibrantly creative, chaotic, challenging, and exciting insights is actually the cultural logic of late capitalism.” Trueman writes —

If, of course, postmodernism, with all of its disdain for history in any traditional sense, is the ideology of advanced consumerism, then it can just as easily be described as the quintessential ideology of modern America; indeed, in modern America, and in the West which follows America's social and economic lead, it is surely interesting to note that just about anything can be believed, however absurd, and any moral precedent can be overturned, however well-established, provided that such action can be successfully marketed as enhancing the American consumerist dream. Whether it is the nature of human sexuality, the definition of marriage, or access to abortion and euthanasia, American public morality is increasingly that of the marketplace, and moral truth is that which the cultural market forces permit, or, in some cases, demand.12

On this view, postmodernism is merely the “late stage of modernity.”13 This accounts for why Trueman elsewhere claims that postmodernism is “fundamentally continuous with modernity in highly significant ways.”14

It is the modernist self, the concept of the self around whom classical liberalism centers, that is responsible for the fragmentation and collapse of the West. To underscore this, Trueman gives an example taken from his own realm of experience, academia. He writes —

For all the talk of the impact of postmodern epistemologies on education, my own belief as one working within the system is that the epistemological discussions within the academy are a side-show to the main event…

…State-funded university theology’s main problem at the moment is not actually one of justifying itself on epistemological grounds but of justifying itself on commercial and economic grounds. The real danger to thoughtfulness, intelligent debate, and real learning comes from the fundamentalist mullahs of management control and consumerism who, not content with having reduced society at large worshipping the false gods of modern materialism, wish to do the same with higher learning. When the purpose of education becomes merely serving the commercial marketplace, Arts subjects in general are placed in grave peril, and theology in particular looks decidedly unstable.15

This helps us understand why it is that Trueman identifies the modernist self as the contemporary self in RTMS. It is a position that he has had for decades.

§IIa. A Historical Pattern

Reaching back at least ten years before his Westminster address in 2008 in a 1998 article titled “Reckoning With The Past in an Anti-Historical Age,” we encounter Trueman’s false equation of postmodernism with “late consumerism” (i.e. late capitalism/modernism). Therein he cites the contemporary anti-historical tendency of the modern (that is to say, contemporary) age as “one of the most significant threats to the Reformed faith.”16

The intellectual roots of the modern anti-historical tendency can be found in the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Whether one looks at the continental or at the Anglo-American tradition, it is quite clear that the rhetoric of the new and the novel quickly becomes associated with the improved and the better.

…in the Enlightenment era an iconoclastic view of history and tradition was seen as part and parcel of the freeing of humankind from bondage and darkness.

Thus, Voltaire, Kant and company were happy to understand themselves as taking part in an ‘enlightenment’ and to surround their work with the language of liberty, while dismissing their predecessors as scholastic, obscurantist, and inhabiting the dark ages. This intellectual tendency toward the exaltation of the new at the expense of the old was massively reinforced with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. At this time new modes of production, urbanisation, and the rise to dominance of the middle classes led to the fundamental reshaping of society and its values.17

Note that in contradiction to what he would later state about the modernist era, here he explains that there was indeed an overriding “optimistic belief in human reason and progress that characterized modernity.” And it is this belief, centering around the modernist self, which is to blame for the cultural decay of the West.

Looking around today it is quite clear that these anti-historical tendencies have reached something of a crescendo in the Western societies of the present time. The advanced consumerism of the West promotes novelty as an absolute virtue. Marx would no doubt have seen this as the result of capitalism's need to be constantly creating new products and new markets for itself. One may hesitate to go all the way with the Marxist analysis of the situation in purely material terms but one cannot deny some truth to such an argument.18

Trueman shares Marx’s criticism of “capitalism’s need to be constantly creating new products and new markets for itself,” once again identifying postmodernism as the ideological counterpart of the “modern consumerist [i.e. capitalist/modernist] society.”19

In his 2005 article “Uneasy Consciences and Critical Minds: What the Followers of Carl Henry Can Learn from Edward Said,”20 Trueman repeats his former arguments about consumerism and postmodernism that he derived from Jameson and Eagleton.21 He also uses the couplet “modernism/postmodernism” to indicate that these are, in essence, the same.22 The article brings together two diametrically opposed thinkers — Henry is on the right, Said is on the left — underscoring the supposed similarities between their driving goal of being an engaged intellectual who can effectuate real social change. Said is presented as offering something of a counterbalance to evangelicals who are too enchanted with consumerism. He writes —

…the enemy at the moment is consumerism, reinforced by the old mythology of Western superiority. These foes are deadlier in many ways than the Red menace if only because they are that much more insidious and seductive . . . . The prophetic voice must speak to this in the coming years if the church is not to become a religious form of wholly secular substance . . . . Evangelicals need to heed the cultural criticism of a Said if they are to avoid a simplistic and idolatrous identification of Christianity with a particular political project, whether of the right or of the left…23

2005 also saw the publication of another article by Trueman titled “American Idolatry,” wherein he examines the eponymous TV show, arguing that it reflects the overall American culture. Once again, the modernist self, i.e. the individualist self, is viewed as the key problem here as it demands everyone and everything cater to its needs. To put the matter simply: The individualistic self championed by modernism destroys culture and society via capitalism which thrives on commodification. Trueman writes —

…the [American Idol] contestants have also grown up in a world where personal value, purpose and self-worth are increasingly understood in solipsistic terms. The whole rationale of libertarian consumerism, upon which our Western economies basically depend, focuses on the centrality of the individual, and his or her needs, as the primary locus of value and meaning. The end result of this is narcissism, the notion that I am singularly important in the grand scheme of things; and consequently anyone who attempts to relativise me, my abilities, or my needs, is blaspheming the god-like importance my narcissism leads me to ascribe to myself.24

[Continued in Pt.3]

Dreher writes —

The ways in which men have forgotten God matter. We have to understand how and why they have forgotten God if we are to diagnose this sickness and to produce a vaccination, even a cure. Unfortunately, the gaze of most Christians cannot seem to penetrate the surface of postmodernity. Many regard the collapse moralistically, as if the tide could be turned back with a robust reassertion of Christian doctrine and ethical rigor.

Dreher thinks that RTMS goes beyond the surface of postmodernism and provides us with a diagnosis of the sickness infecting Western civilization. This implies that he is either ignorant of what postmodernism has taught about the self, or he is on the same page as Trueman, and is, therefore, equally culpable for leading people astray.

Dreher writes —

Ordinary Christians need — desperately need — a profound and holistic grasp of the modern and postmodern condition. It is water in which we swim, the air that we breathe.”

Dreher distinguishes between modern and postmodern, but speaks as if the two constitute a singular condition we can observe around us, stating that it, singular, is inescapably all around us. This is just as ambiguous as Trueman’s use of the word modern throughout RTMS.

Trueman writes —

They [that is, people who would use, and understand to be meaningful, assertions like “I was assigned the wrong gender”] are ordinary people with little or no direct knowledge of the critical postmodern philosophies whose advocates swagger along the corridors of our most hallowed centers of learning.”

Note that his admission here contradicts his earlier views on postmodernism as an overblown movement whose claimed “epochal significance” is uncertain.

Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford, 2002), 13. (emphasis added)

Butler does not explicitly delve into the postmodern privileging of narrative over propositions, but this is implied by his statements regarding grand-narratives being discarded of and replaced with local narratives which are all subject to negotiation.

Later, Butler explains —

Postmodernist thought sees the culture as containing a number of perpetually competing stories, whose effectiveness depends not so much on an appeal to an independent standard of judgement, as upon their appeal to the communities in which they circulate – like rumour in Northern Ireland. As Seyla Benhabib points out, for Lyotardians:

“Transcendental guarantees of truth are dead; in the agonal struggle of language games there is no commensurability; there are no criteria of truth transcending local discourses, but only the endless struggle of local narratives vying with one another for legitimation.’

— Postmodernism, 29.

“Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light,” in Westminster Theological Journal 70 (2008), 2. (emphasis added)

See Pluckrose, Helen. “No, Postmodernism is Not Dead (and Other Misconceptions),” Aero, July 2, 2018, https://areomagazine.com/2018/02/07/no-postmodernism-is-not-dead-and-other-misconceptions/.

Rage, Trueman, 2-3.

Trueman writes —

I myself prefer to speak of the cultural logic of advanced consumerism so as to avoid the prescriptive political and eschatological implications of Jameson’s Marxism, but his basic point is, I believe, sound. To defend this thesis would take too much time today, so a single quotation from Karl Marx himself will have to suffice. In the Communist Manifesto Marx describes with unnerving foresight the epistemological and ethical anarchy which modernity, extended to its very limits, globalized, and universalized, will bring with it:

‘The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe.... Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all newformed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.’

All that is holy is profaned: pardon the pun, but full marks to Marx for here predicting precisely the kind of anarchic world which would produce both the highly sophisticated philosophical hedonism of Michel Foucault and the crass redneck shenanigans of the Jerry Springer Show.”

—Rage, Trueman, 3.

[Note that his use of consumerism does not change the essence of what is being said. It is a distinction without a difference that merely sounds less Marxist.]

As Dino Felluga explains —

“Commodification” is the subordination of both private and public realms to the logic of capitalism. In this logic, such things as friendship, knowledge, time, etc. are understood only in terms of their monetary value. In this way, they are no longer treated as things with intrinsic worth but as commodities. (They are valued, that is, only extrinsically in terms of money, in terms of a universal equivalent.) By this logic, a factory worker can be reconceptualized not as a human being with specific needs that, as humans, we are obliged to provide but as a mere wage debit in a businessman’s ledger.

—Critical Theory: The Key Concepts, (New York: Routledge, 2015), 50-51.

Rage, Trueman, 3. (emphasis added)

See Trueman, Carl R. “The Most Important Philosopher Of Whom You Have (Probably) Never Heard,” The Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, Nov 19, 2020, https://cbmw.org/2020/11/19/the-most-important-philosopher-of-whom-you-have-probably-never-heard/.

“The Importance of Being Earnest: Approaching Theological Study,” in Themelios 26.1 (Autumn 2000), 41.

ibid. (emphasis added)

Themelios, 23.2 (February 1998), 29.

ibid., 30. (emphasis added)

ibid., 31. (emphasis added)

ibid.

In Themelios 30.2 (Spring 2005).

Footnote 16 —

I am also persuaded by the arguments of Frederic Jameson, Perry Anderson, and Terry Eagleton (and articulated in a Christian context by individuals such as Stanley Hauerwas) that there is a connection between postmodern relativist epistemologies and consumerism.

Uneasy Consciences, Trueman, 45.

ibid., 42.

ibid., 44. (emphasis added)

Reformation 21, Aug 25, 2005, https://www.reformation21.org/counterpoints/post-21.php.

(emphasis added)