I. Organicism’s Fraternal Twin: “Christian” Integralism

Christian Nationalism, being derived from an admixture of Thomistic and Romantic philosophy, bears many similarities to Roman Catholic Integralism. The political philosophy of Integralism is only one aspect of a larger philosophy of integralism espoused by Roman Catholic thinkers. Wilfred G. Lauer explains this in his article Christian Integralism. Lauer writes —

We have a word in “Christian Integralism” that seems to sum up, and from which we can expand our whole view of the universe. To be integral means to be whole. To be whole means to be holy. To be whole and holy means to be happy. To be holy and happy is the end of our being.

[…]

Man is a dependent creature and so finds his wholeness in dependence. Man’s body with its senses depends upon physical things. Man’s soul with its powers depends upon the body and senses. Man’s body and soul are mutually dependent and complement each other but are still dependent, because man depends, body and soul, on others to fulfil his corporal and spiritual needs.1

Under this overarching philosophical view, the fall of man “cut off at the very source the integrating force that made [man] one and whole. Then with the key of integrity lost, his faculties of mind and senses of body each sought their own ends, independently of the whole man, independently of others, independently of God.”2

“Christian Integralism,” then, teaches that all things are to be integrated under God, via hierarchical arrangements of dependence. The individual man is not complete in himself but is necessarily dependent upon others for the constitution of his self, a constitution that occurs through man’s production of material goods not for profit but for the greater good. Lauer explains —

…man becomes integral by the work of his soul and body on the material world about him, by shaping it with love for the needs of others and by offering his work to God, his Father. In so doing he finds personal integrity by the joint work of soul and body; he finds social integrity by the joint work with, and for, others…Man becomes integral by becoming a complete person. He becomes a complete person by extending his personality to other men, to the things he makes, and by dedicating his person and all that he has and does to God, his Father.3

On this view, the reintegration of man is a result of the work of the Holy Spirit whom the Father and Son sent after the resurrection and ascension of Christ. This is because, Lauer explains, the Holy Spirit entering “the souls of men” made “them one with each other and with Himself, living on mystically in men, extending Himself in time and space, taking to Himself new hands and feet, new minds and hearts.”4

According to the Integralists, therefore, the integration of man and society is achieved solely through the work of the Spirit of God received by individuals who believe the Roman Church’s dogmas, and who engage in her liturgical and sacramental practices. There can be no separation between Church and State because, as Edmund Waldstein states, integralists view “political authority as ordered to the common good of human life, that rendering God true worship is essential to that common good, and that political authority therefore has the duty of recognizing and promoting the true religion”5 (i.e. the Roman Catholic religion).

Indeed, as Timothy Troutner explains, Integralists believe that “a just social order cannot exist unless political regimes acknowledge Christ’s authority, place their temporal power at the disposal of the spiritual power, and become provinces of a united Christendom.”6 For Integralists, “the Church’s supreme authority [is] thought to provide the integrating principle that [will] restore the differentiated, hierarchical social system that had been weakened by modern economic, political, and cultural developments in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century.”7

Integralism is not the dominant political philosophy of most Roman Catholics, but that does not mean that it is innocuous. Given the growing influence of Roman Catholic Integralist scholars like Adrian Vermeule, Edmund Waldstein, Thomas Crean, and Alan Fimister it is evident that there exists a large audience of Christians – even if in name only – who resonate with the Integralist philosophy. Chief among them we find the Christian Nationalist movement, most fully articulated and fleshed out by Stephen Wolfe and Doug Wilson, which embraces a form of theocratic communitarianism headed by a central “Christian” Prince.”8

Moreover, despite the fact that the Eastern Orthodox do not view themselves as under the pope of Rome’s authority, they share in common with the Integralists and the Christian Nationalists a communitarian anthropology, sociology, and preference for a “Christian” Monarch. This not only lends increased support for a “Christian” monarchic communitarianism that subordinates the individual’s freedom of thought, speech, and action to the collective (which contradicts reason and Scripture), but also encourages ecumenism under the pretense of letting grace perfect nature.9

II. The Historical Trajectory of Rome

As has been mentioned above, Integralism is not the dominant form of Catholic political thought. However, it is gaining prominence today. Why that is the case needs to be given some consideration. In short, when the Reformation occurred the Roman Catholic church’s ecclesiastical and political authority began to wane. The decrease of Roman Catholic ecclesiastical and political authority contributed to the “secularization” of the West,10 which created the intellectual, political, and economic opportunities necessary for the Enlightenment to take place. For many Roman Catholics, the Protestants were ultimately to blame for the Enlightenment and the cultural and religious damages it supposedly wrought, for without the Reformation’s emphasis on the individual’s moral and intellectual autonomy, the Enlightenment would not have taken place, the unity of the State and the Church would have remained in tact, and the unity of individual churches under the authority of the Roman Church would have been preserved. Lauer opines11 that “the Protestant Revolt…drew man from God’s authority and gave birth to individualism.”12 It did this by leading to

…the Industrial Revolution which drew man from making things for use, to make them for profit. [And] disintegrated man’s body and soul for he no longer used soul to command his body in the use of tools, but became instead the tool of a tool. And so to-day man no longer controls the use of the tool, but the capitalist owns and controls the use of the machine and buys man on the labour market to man the machine: and as a result man is unmanned, becoming a machine and not a man, becoming a thing and not a person.13

Indeed, because of Protestantism the argument goes, “individualism has disintegrated man socially so that he no longer finds his completion and wholeness in union with his fellowmen.”14

Thus, the Christian Nationalists follow the Romantics to Enlightenment philosophy’s emphasis on individualism, placing the blame for the disintegration of society on the Enlightenment, whereas the Roman Catholic Integralists place the blame largely on the Protestant “Revolt.” Nevertheless, as we have shown elsewhere,15 the Roman Catholic Church and Protestants began to create somewhat of a unified philosophical front against what they both viewed as the main problem facing the West during the mid-1800s to early 1900s — a capitulation to the rising tide of secularization across all areas of life. Roman Catholicism did this by giving a renewed emphasis to the teachings of Thomas Aquinas on matters related to anthropology, society, politics, and economics.16 As James Hennesey explains —

Roman Catholicism was defensive and increasingly [culturally and sociopolitically] isolated. It drew inner strength from growing pietism (in reaction to prevalent rationalism) and from emphasis on the spiritual authority of the pope. Structurally, power shifted from the world’s bishops toward Rome. Intellectuals and universities were suspect.17

This turn to Thomism may seem to have been a turn toward a philosophical system that encourages reason and independent and free intellectual investigation, however that was not the case. For as Henessey further explains —

[French historians] have pointed to the continuity between the Thomistic revival and the romantic-traditionalist current prevalent at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Both sought authority in religion and philosophy and limited severely the rights of individual reason. The complaint to be cured was “the disasters produced by the individualism of the human spirit left to itself.” And...it was all done in an era when the historicity of philosophy was not yet appreciated, nor the need to see philosophical problems in historical context.18

Thomism and Romanticism are once again brought together to fight the Enlightenment, attacking ideas like individualism, capitalism, and freedom of speech.

III. The Dialectics of Political Romanism

What is more, the response to “modernity” was not limited to a renewed emphasis on “pure” Thomism. Rather, as Sarah Shortall explains, Roman Catholics at this time “developed two main theological responses to modernity and the secularization of public life—one Thomist and one broadly patristic.”19 The Thomistic response which have briefly touched on above came under scrutiny from some theologians because it “could be, and was, deployed to serve a range of competing political projects.”20 The range of political projects was so broad that theologian “[Henri] de Lubac... recalled in his memoirs that he had known ‘a Thomism as patron of the ‘Action française,’ a Thomism as the inspiration of Christian Democracy, a progressive and even a neo-Marxist Thomism.’”21 Nouvelle Théologie thinkers like de Lubac sought to address the Neo-Thomist separation of the church and the state by returning to the early church fathers, and by engaging with counter-enlightenment philosophers like Hegel, the dialectical philosopher of synthesis.

Among these theologians, we find one of Pope Francis’ greatest influences, Gaston Fessard a scholar of Hegel noted for creating a dialectical interpretation of Ignatius of Loyola’s key theological work The Spiritual Exercises. Shortall notes that Fessard

...developed an immanent critique of Marxist materialism, turning Marx against Lenin in order to recover a variant of Marxism capable of entering into meaningful conversation with Catholicism.22

Fessard was deeply engaged with “nineteenth-century German philosophy,”23 and authored “one of the earliest systematic analyses in French of Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts, which had only just been discovered”24 during Fessard’s time. He also fused “St. Paul and Hegel,”25 arguing that

...both the individual person and history as a whole are governed by a “Jew-Gentile dialectic” that raises human beings from particular communities up to the universal unity of the mystical body of Christ. Just as Christ had overcome the opposition between Jew and Gentile in his own person, according to Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians, each person must repeat the same process. Each Christian had to overcome the opposition between their inner Jew and Gentile so as to become a Christian “person” in whom the particular and the universal coincide—a unique “me” who is also “an irreplaceable part of an organic whole: the mystical Body of which Christ is the Head and we are the members.” And Fessard applied the same logic to collective persons such as the family, nation, and the community of nations, which he labeled “moral persons,” to show how these communities could reconcile the demands of internal solidarity with their duty to the larger communities in which they were embedded.26

Once again the same problems are identified; and the same sources and their attendant ideas are referenced and utilized as a corrective to the problem of “modernity.” Thomism and counter-enlightenment philosophy are synthesized in order to reunite what modernity had broken up into atomistic fragments,27 including the Church and the State.

Nouvelle theologians like Fessard sought to find a political “third way” that “could operate transversally to the reductive and inadequate dichotomies they believed were offered under the terms of the modern political economy.”28 Yet while they technically rejected Integralism, they nonetheless believed that “the spiritual enlivens and infuses all social life, and thus that politics was in essence theological, and vice versa.”29 Thus, these thinkers rejected the strict distinction between the earthly and the spiritual in order to further penetrate the social order. As Timothy Howles explains —

…their eschatology guarded against a premature unification of the world by secular ideologies and credos, it also set forth a vision of what Christians could and should be working for in the present, namely, the advent of a reconciled humanity. Immanent political order was thus to be desired and worked towards, but only as a shadow or proleptic anticipation of the true unity that was to come.30

Graham Mcaleer is correct in noting that “John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis” were influenced by these theologians, and taught that the “church addresses politics not by involvement in state power but by public persuasion.”31 However, this does not preclude the reconciliation of their thinking with that of the Integralists.

Integralism, like Wolfian-Wilsonian Christian Nationalism, teaches that “Christian peoples cannot be properly governed unless the state is completed politically by the [“Christian”] Church.”32 Mcaleer notes that this is because —

Integralist political theory does not take its origin from law, personalist phenomenology, or a state of nature postulate, but from the metaphysical claim that natures have ends to which actions must conform. The final end of human nature is supernatural and therefore politics is not complete unless integrated with the rule of the legitimate representative on earth of the supernatural, the Catholic Church under the leadership of the successor to St. Peter, the pope.33

Like Wolfian-Wilsonian Christian Nationalism, moreover, the Integralist philosophy is organicist, envisioning “society…not [as] the coming together of discrete, autonomous parts for mutual projects, but more like a rose, a singular unity unfolding and relaxing into so many connected iterations.”34 While some Romanists have tried to maintain a strict distinction between the Neo-Thomist and Nouvelle theologians and their understanding of how the Church and State are related, we see in the contemporary politics of Rome a synthesis of Thomism and Romanticism (Counter-Enlightenment philosophy).

IV. The Papal Dialectic and Its Telos

The Roman Church is dogmatically committed to many ideas undergirding Integralism,35 while simultaneously dogmatically committed to a kind of dialecticism that leaves open room for an incrementalist approach to achieving the Integralist goal. As Ethna Regan explains, Pope Francis, a successor of the Nouvelle theologians,36 advocates for political principles like “unity before conflict, [and] the whole before the part…”37 The Hegelianism he received through the Nouvelle theologians, particularly through the writings of Gaston Fessard, can be heard in his declaration concerning what this unity is and how it is to be achieved. He states —

Solidarity, in its deepest and most challenging sense, thus becomes a way of making history in a life setting where conflicts, tensions and oppositions can achieve a diversified and life-giving unity. This is not to opt for a kind of syncretism, or for the absorption of one into the other, but rather for a resolution which takes place on a higher plane and preserves what is valid and useful on both sides.38

The pope is describing a process of sublation in which what is useful is preserved on both sides of a political contradiction/conflictual political relationship, and what is not useful is discarded of/canceled out. History is made by this process, which is itself brought about by solidarity, and thus makes solidarity between conflicting putatively Christian groups — e.g. Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant — not only inevitable but necessary for the progress of history. Thus, Regan writes —

An unsettling of political binaries is a common feature of Francis’ thought; indeed, it seems a deliberative strategy derivative of his dialectical approach. His sometimes illiberal, other times radical, approach to issues means that Francis cannot be definitively claimed by conservatives or liberals, thus offering a distinct perspective useful for dialogue in a pluralistic context.39

Francis has openly criticized Integralism proper,40 nevertheless this does not mean that Integralism is completely out of the picture, seeing that, as Roman Catholic philosopher Massimo Borghesi argues, the current pope is a “thinker who has drawn on numerous Church thinkers of the 20th century to seek a “third position” between conservatism and progressivism. ...[and]…‘a mystic’ who sees his mission as resolving these tensions.”41

Francis’ perceived role, therefore, is to synthesize opposed political stances, preserving what is useful and discarding what is not, in order to achieve unity, or integrity. The kind of integrity he has in mind, however, goes beyond simply political unity, extending to every aspect of created life. Echoing the “Christian Integralism” of Wilfred G. Lauer, Francis argues that the full/integral development of man means the integration of all people groups through viable models of social integration, of human systems (e.g. the economy, culture, family life, and religion), of the individual and the collective, and of the body and soul.42 What is being articulated here is in line with Integralism, despite Francis’ rejection of the political philosophy. It is a Roman Catholic form of organicism which echoes many of the same ideas expressed by Wolfian-Wilsonian Christian Nationalism, in its rejection of classical liberalism.

Along with Christian Nationalism, Francis’ political teaching critiques liberalism as embracing an economic philosophy (viz. capitalism) that alienates man from the products of his own hands and exacerbates the atomizing problem of individualism via consumerism, attacks the authority of the family, the church, and the state, and is responsible for the social ills which are destroying the modern world. What is more, as Ole Jakob Løland explains, Francis, like Wolfe and Wilson,

…exemplifies his vision of a people with a village, this small entity that evokes associations with proximity, reciprocity, and close human relations. In the Pope’s theology, there appears to be a pattern whereby the greater distance the individual finds itself at from its family, its culture, and its roots, the greater is the risk of falling prey to the cardinal sins of the liberal ethos of globalization: Individualism, hedonism, consumerism, and materialism. As the Pope admonishes: “We need to sink our roots deeper into the fertile soil and history of our native place, which is a gift of God” (EG, no. 235)43

As Løland further notes —

The organic view of the people that sometimes characterizes populist conceptions of the people here takes shape in Pope Francis’ discourse. The people becomes a person-like organism and a living being with a soul and an awareness formed through experience that results in a personality.44

Indeed, “the Pope’s definition of a people lends itself to romantic, nostalgic, and identitarian understandings of it,”45 further demonstrating the many parallels between his thinking and that of the Christian Nationalists.46 The significance of this lies in the fact Francis is capable of, on the one hand, working in concord with the Christian Nationalists while, on the other hand, transitioning them to another political system altogether – a political system which is the synthesis of classical liberalism and progressivism, individualism and collectivism, capitalism and communism, decentralization and complete centralized control. Is there such a system? Yes, that which is being proposed by the World Economic Forum.

V. Ordo Ab Chao – How Christian Nationalism and Integralism Aid the Great Reset

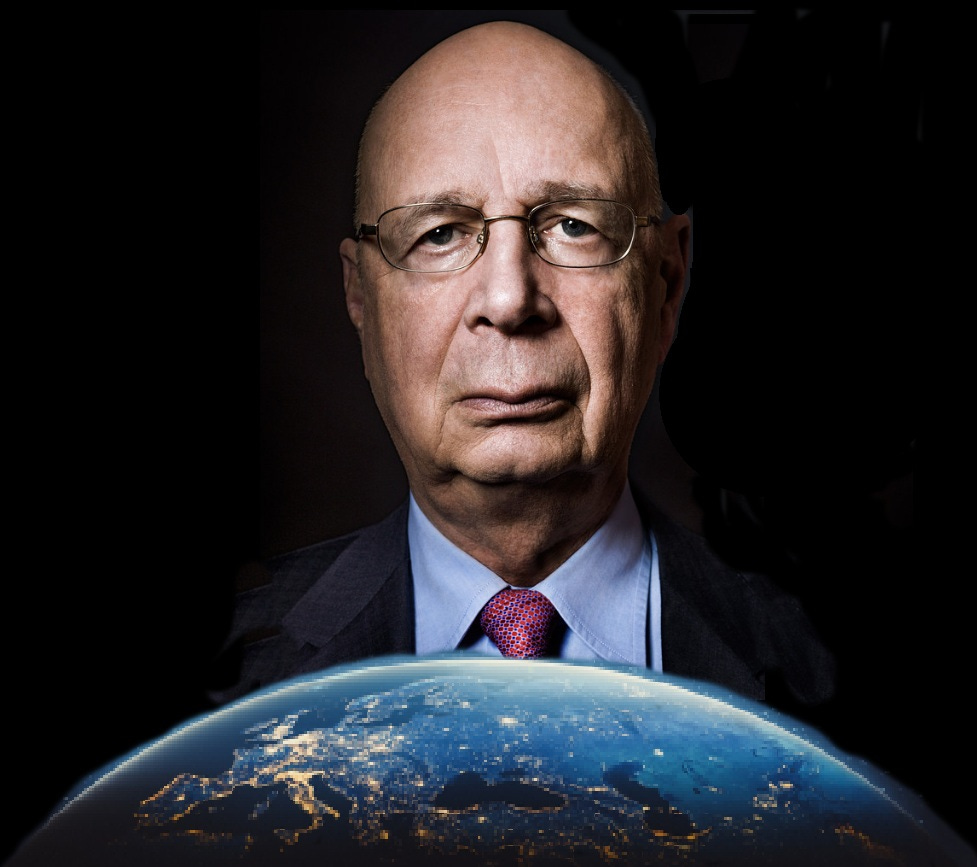

To many Christian Nationalists, Roman Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox proponents it may seem absurd to suggest that they are unwittingly being pushed in the direction of supporting the World Economic Forum’s dystopian future. However, when we look at what Klaus Schwab and the WEF members are envisioning for the future, we see that there is a considerable amount of overlap. For instance, like Klaus Schwab and the World Economic Forum, Christian Nationalism, Integralism, and Eastern Orthodoxy are all opposed to classical liberalism, and for some of the same key reasons. Klaus Schwab writes –

From Austria, France and the United States, to Poland, the Philippines, and Peru, illiberal populists are on the rise.

…The problem is political, not just economic. Liberal democracy is humankind’s greatest political achievement. Yet liberal democrats around the world are reluctant to make the case for it. No wonder they are losing the battle for citizens’ hearts and minds.

The problem is far from new. In fact, it is at the very root of liberalism. Wary of censorship or oppression, liberal thinkers have more often than not espoused moral neutrality: they do not advocate a single set of values, or a particular definition of what constitutes a good life. A liberal society – almost by definition – enables its citizens to lead any life they wish, as long as third parties suffer no harm.47

Schwab’s criticism of classical liberalism is that while it is a great political achievement, it needs to be reshaped because it lacks a single set of values, a definition of what constitutes a good life, and enables its citizens to freely choose the manner of life they live, given that they do their neighbor no harm. The solution to this, he argues, is a shared understanding of us. He writes —

Liberal democrats need to make it clear that we get nowhere by blaming others, and that assuming shared responsibility is the only way to build a better shared future. …indispensable is the moral conviction, passionately expressed, that the “immigrant's daughter who studies in our schools” is a genuine member, with full rights, of that common us.48

What the West needs, in other words, is a new political system which unifies people around a set of shared values. While it is true that the values upheld by the WEF are not identical to those of the Christian Nationalists and Integralists, their disagreements are not foundational but superficial. What is common to these groups is a view of society as lacking social cohesion because of a morally neutral political liberalism which promotes individualism and lacks a shared set of moral values. What is also common to them is the belief that the problem of societal fragmentation can only be remedied by “collective action and collectivism, dialogue,”49 assisted, of course, by religion.50

While it is true that the Great Reset concerns the so-called “global community,” that does not mean that it is unconcerned with local communities. Instead, the WEF argues that localism benefits its stakeholders by allowing them to “draw on, local expertise and evidence, in recognition of the influence and knowledge that communities hold.”51 It is in the best interest of the WEF, in other words, for communities to retain their local traditions, trades, institutions, and how-to knowledge. This applies within the realm of religion as well, seeing as, according to the WEF, “religion gives people the opportunity to share common values, create a sense of unity and encourage a sense of community.”52

Thus, they argue that “horizontal governance, governing by including the public, should be implemented.”53 Horizontal governance operates “through networks in place of hierarchies; through interdependence rather than power relationships,”54 as Daniel Ferguson argues, but this does not eliminate vertical governance within the community itself. For as Ferguson also notes, “horizontal initiatives cannot replace or operate without final review and approval by the department or agency.”55As a communitarian approach to governance, horizontal governance reflects the concepts of Sphere Sovereignty (Christian Nationalism) and Solidarity (Integralism). For all three approaches, institutions are internally vertically governed but externally horizontally governed.

Schwab believes this communitarian approach is necessary because individualism has led to a breakdown in our morals. Echoing the thinking of Christian Nationalists and Integralists, Schwab believes that “each individual is embedded in societal communities in which the common good can only be promoted through the interaction of all participants – and business success is also embedded in this interaction.”56 He, like them, argues that “we have witnessed the gradual erosion of [the] communitarian spirit over recent years.”57 Further echoing the criticisms of classical liberalism, Schwab argues that it is a loss of the communitarian spirit pushed along by free market capitalism that

…transformed [enterprises] from a purposeful unit to a functional unit: the purpose of an enterprise – to create goods and services for the common good – in society has been replaced by a purely functional enterprise philosophy, aimed at maximising profits in the shortest time possible with the aim of maximising shareholder value.

…In this context, the enterprise is no longer an organic community; it becomes a functional “profit-generating machine”. All parts that do not fulfil their purpose are replaceable: managers, employees, products, locations.

…This has consequences for individual behaviour: one cannot expect anything but selfish thought and action from somebody who knows that he or she is replaceable at any time. Instead of a communitarian sense of duty, there is a rise of individualistic profit-seeking behaviour in which society plays only a secondary role.58

The culprit here is the same – classical liberalism, capitalism, and individualism. These must all be changed, according to Schwab, if we want to see human societies flourish in the 4th Industrial Revolution. This is why the WEF treats religious institutions as playing a role in the Great Reset, including promoting the notion of human-nature interdependence, countering economic fundamentalism (i.e. undermining capitalism), promoting holistic (i.e. organicist/integralist) notions of the human self, bringing about a “communitarian impact,” and monitoring businesses (“agents”) in society.59

VI. Concluding Remarks

Whereas Christian Nationalists view themselves as providing a means of fixing the West, its underlying beliefs, prime sources, and commitments are not only non-Christian in origin, but in line with those of the very groups they believe themselves to be fighting against. At their root the left and the right declare that the original state of society is an organic or integrated whole, that individualism is to blame for the dis-organization/dis-integration of society, that the self is the product of one’s linguistic/dialogical interactions with others as mediated through various institutions, that liberalism and capitalism are to blame for the breaking down of social bonds in order to exploit workers, that modern man is alienated from the fruit of his labor by corporations who have devalued personal labor by reducing it to a mere money making enterprise that does not take into consideration “the common good,” that there is a need to bury the current “liberal order” which died at the hands of hypocrites and corrupt politicians, and resurrect a communitarian social body that will ascend to the heavens.60

Given the ecumenist leanings of Christian Nationalists like Stephen Wolfe, Doug Wilson, and Andrew Torba, and given the ecumenist leanings of the papacy, their eventual collaboration in establishing a neo-feudalist society seems inevitable. The problem, however, is that Pope Francis is a dialectical political philosopher who believes that his job is to bring about a synthesis of the conservatives and the progressives, individual and community, capitalism and communism, the old world order and the new world order. Francis explains that he wants to conserve what is useful and discard of what is not useful, and in the context of his relationship to Klaus Schwab and the Great Reset, that which is not useful is that which will hinder the progress of the 4th Industrial Revolution. Christian Nationalism not only fails to attack the progressivist/identitarian left, because they cannot do so without destroying their own philosophical foundation, but positively aids the Great Reset and 4th Industrial Revolution by championing and mainstreaming the very anti-biblical, irrational, and anti-reality concepts Klaus Schwab and his WEF cronies believe need to be in place in order for their neo-feudalistic, tyrannical technocratic vision of society to manifest.

Is this the way forward, “Western Man”? Or is it a delusion of men whose grasp for power exceeds their capacity to grasp and utilize wisdom? Is it the fruit of truly informed men who will lead God’s people well and thereby benefit society as a whole? Or is the fruit of malformed thinking that will lead God’s people on a collision course with a supra-national organization that only sees all Christians as useful idiots they can employ to unwittingly do their bidding? Think about these questions well, for on the day of judgment you, and you alone, will have to give an account to God.

The Irish Monthly, Vol. 70, No. 823 (Jan., 1942),16-17. (emphasis added)

ibid. (emphasis added)

ibid., 17. (emphasis added)

ibid., 18.

“What is Integralism Today?”, Church Life Journal, Oct 31, 2018, https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/what-is-integralism-today/.

“The New Integralists: What they get wrong, and why we can’t ignore them”, Common Weal Magazine, Oct 28, 2020, https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/new-integralists. (emphasis added)

Reno, R.R., “Liberal Integralism”, First Things, Mar 14, 2018, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2018/03/liberal-integralism.

Under Integralism, the Pope can be the head of state and the head of the church. One could argue, in fact, the situation is the same under Catholic social teaching, albeit in an “indirect” manner. For more on the distinction between the direct and indirect power of the church, see Love, Thomas T. “Roman Catholic Theories of ‘Indirect Power’”, in Journal of Church and State Vol. 9, No. 1 (1967), 71-86.

Andrew Torba and Andrew Isker’s ecumenism makes this clear,

when they write —

We are thankful to our Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox brothers and sisters who have inspired us to publish this book. We recognize and respect one another’s differences and unite in our shared love of Jesus Christ our King. We realize that we have a shared enemy of competing antichrist worldviews that hate our King.

—Christian Nationalism: A Biblical Guide to Taking Dominion and Discipling Nations, 77.

Additionally, like Torba and Iskar, Doug Wilson, another prominent Christian Nationalist, holds to a politically expedient form of ecumenism. See Stivason, Jeffrey. “Doug Wilson and Covenant Objectivity”, A Place for Truth, April 18, 2022, https://www.placefortruth.org/blog/doug-wilson-and-covenant-objectivity.

See Ditmar, Jeremiah, et al. “The Religious Roots of The Secular West: The Protestant Reformation and The Allocation of Resources in Europe”, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Oct 31, 2017, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/religious-roots-secular-west-protestant-reformation-and-allocation-resources-europe.

For a much longer treatment of this Romanist interpretation of history, see Charles Taylor’s work A Secular Age, in which he fleshes this polemical argument out over the span of 896 pages.

Christian Integralism, 20.

ibid.

ibid. (emphasis added)

See Diaz, Hiram R. “The Myth of Excessive Individualism and the Road to Christian Nationalism,” Sovereign Nations, May 4, 2023, https://sovereignnations.com/2023/05/04/myth-of-excessive-individualism-to-christian-nationalism/.

See Pope Leo XIII’s papal encyclical, “Aeterni Patris:On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy”, Vatican, https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_04081879_aeterni-patris.html.

“Leo XIII's Thomistic Revival: A Political and Philosophical Event”, in The Journal of Religion Vol. 58 (1978), S191.

ibid., S197. (emphasis added)

Soldiers of God In A Secular World, 8. (emphasis added)

ibid.

ibid. (emphasis added)

ibid., 64-65. (emphasis added)

ibid.

ibid.

ibid., 76.

ibid., 76-77. (emphasis added)

For more on Fessard’s dialecticism, see Muir, Mary Alice. “Gaston Fessard, S. J., His Work Toward A Theology of History”, MA Thesis, Marquette University (1970).

Howles, Timothy. “Political-Theological Diagonalizations: A Review of Sarah Shortall’s “Soldiers of God in a Secular World”, Voegelin View, Oct 9, 2022, https://voegelinview.com/political-theological-diagonalizations-sarah-shortall-soldiers-of-god-in-a-secular-world-review/.

ibid.

ibid.

“A Wokeness for Rad Trads”, Law & Liberty, Nov 24, 2020, https://lawliberty.org/book-review/a-wokeness-for-rad-trads/.

ibid.

ibid. (emphasis added)

ibid. (emphasis added)

See Camosy, Charlie. “Reconciling integralism, the magisterium, and the modern world”, The Pillar, Sept 2, 2022, https://www.pillarcatholic.com/p/reconciling-integralism-the-magisterium-and-the-modern-world.

See Wooden, Cindy. “Pope Francis says Vatican II shaped his theology”, The Tablet, Sept 30, 2021, https://www.thetablet.co.uk/news/14567/pope-francis-says-vatican-ii-shaped-his-theology.

“The Bergoglian Principles: Pope Francis’ Dialectical Approach to Political Theology”, in Religions 10 (2019), https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/10/12/670. (emphasis added)

ibid. (emphasis added)

ibid.

See O’Connell, Gerard. “Pope Francis: ‘Build bridges, not walls’”, America: The Jesuit Review, Mar 31, 2019, https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2019/03/31/pope-francis-build-bridges-not-walls.

Pentin, Edward. “Author: Pope Francis Is a ‘Mystic’ Trying to Solve Left-Right Dichotomy in the Church”, National Catholic Register, April 21, 2018, https://www.ncregister.com/news/author-pope-francis-is-a-mystic-trying-to-solve-left-right-dichotomy-in-the-church. (emphasis added)

See “Audience with the participants in the Convention organized by the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development on the fiftieth anniversary of ‘Populorum Progressio’, 04.04.2017”, Vatican Press, April 4, 2017, https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2017/04/04/170404a.html.

The Political Theology of Pope Francis: Understanding the Latin American Pope, (New York: Routledge, 2023), 83. (emphasis added)

ibid. (emphasis added)

ibid. (emphasis added)

In another point of agreement with Wolfe, Francis’ theology and political philosophy embraces various aspects of the Phenomenological school of philosophy. See Oltvai, Kristóf. “Bergoglio among the Phenomenologists: Encounter, Otherness, and Church in Evangelii gaudium and Amoris laetitia”, in Open Theology, Vol. 4 (2018), 316-324.

“Why liberals are losing the battle for citizens’ hearts and minds”, June 7, 2016, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/why-liberals-are-losing-the-battle-for-citizens-hearts-and-minds/. (emphasis added)

ibid.

Engaging Citizens for Inclusive Futures Rebuilding Social Cohesion and Trust through Citizen Dialogues, World Economic Forum (2021), 3, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Citizen_Perspectives_on_a_Just_Great_Reset_2021.pdf.

ibid.

ibid., 8.

ibid., 16. (emphasis added)

ibid., 21. (emphasis added)

Understanding Horizontal Governance, The Centre for Literacy, (Montreal: 2009), 2, http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/sites/default/files/CTD_ResearchBrief_Horizontal%20Governance_sept_2009_0.pdf.

ibid., 1. (emphasis added)

“Klaus Schwab – A Breakdown in Our Values”, World Economic Forum, Jan 7, 2010, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2010/01/a-breakdown-in-our-values-klaus-schwab/. (emphasis added)

ibid.

ibid. (emphasis added)

See “The Role of Faith in Systemic Global Challenges”, World Economic Forum, June 2016, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC16_Role_of_Faith_in_Systemic_Global_Challenges.pdf, 7-8.

For example, see Haywood, Charles. “On Space”, The Worthy House, July 13, 2019, https://theworthyhouse.com/2019/07/13/on-space/.

Very helpful to me, as I knew that statements of “Teaching for Transformation” being “integrally and Authentically Christian” were philosophical, I didn’t know what they meant:

“The TfT program, as developed by Prairie Centre for Christian Education and partner schools, provides a frame-work for the development of authentic and integral Christian learning experiences that are grounded in a transformational worldview with a focus on seeing and living out God’s story.”

From: https://www.pcce.ca/resources/Documents/PCCE-Educators-Documents/TfT/2017-18%20TFT%20Brochure.pdf

TfT is distributed in the unites States by the Center for the Advancement of Christian Education located at Dordt College in Iowa

See here: https://www.teachingfortransformation.org/who-we-are/tft-story