Pushing the Synthesis

Properly Understanding the Roots of "Christian" Nationalism

I. A Brief History of Thomistic Romanticism

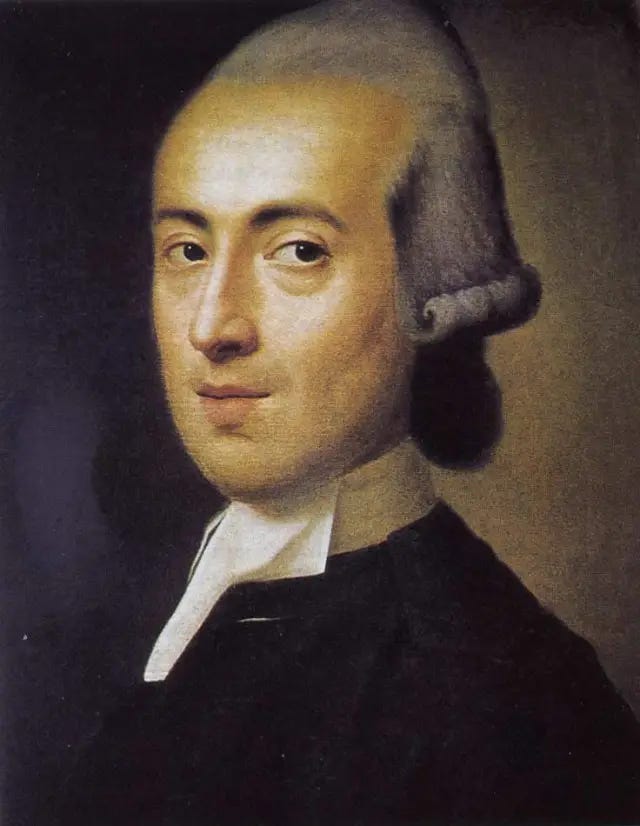

The temptation to accept philosophical ideas at variance with biblical teaching has always been there for Christians, and seems to intensify during difficult times. Currently, many Christians are embracing a hybrid philosophy comprised of elements of Thomism and counter-enlightenment philosophy.1 This philosophy, which we will call Thomistic Romanticism, found initial pragmatic expression in the 1800s, when Protestant theologians, among them the famed Abraham Kuyper, began incorporating ideas from counter-enlightenment thinkers like Johann Gottfried Van Herder and G.W.F. Hegel into their theologies.2

Shortly thereafter, French Catholic philosophers of the Neo-Thomistic and Personalist schools of thought would acknowledge not only the significance of Hegel’s philosophy and their need to engage with him, that Hegel’s “system presents so striking a resemblance with those of the Scholastics that one might be tempted to believe he has borrowed directly from them.”3 This was likely due to their sharing of a common source in Aristotle’s philosophy, although they deviate from one another in some important ways, respecting their concepts of organism, teleology,4 historical dialecticism,5 and the development of the self by external and social means.6 Thomistic Romanticism would later be given firmer shape by the Nouvelle Théologie, a theological movement whose leaders “played a pivotal role in the French reception of Hegel, Heidegger, and the early writings of Marx,”7 blending elements of Hegelianism with Thomism,8 and, ultimately, influencing Pope Francis’ “dialectical theology.”9

We began by laying out this rough sketch of Thomistic Romanticism’s history for several reasons. Firstly, Thomistic Romanticism has recently become more visible with the advancement of Christian Nationalism as articulated by authors Stephen Wolfe and Doug Wilson. Secondly, therefore, seeing as Thomistic Romanticism is neither Christian nor Protestant, then it follows that those promoting Christian Nationalism as the classical Protestant view are, in fact, either greatly mistaken or deceiving their audiences about the origins of that political theory. Thirdly, it helps prepare the reader for what will follow in our last article — A demonstration that Thomistic Romanticism, which is part and parcel of Christian Nationalism, logically leads to two outcomes which are inimical to Christianity: Integralism and the Great Reset.

II. The Case for Thomistic Romanticism

In The Case for Christian Nationalism, Stephen Wolfe’s assumed10 anthropology is Thomistic, in which man is necessarily and essentially a rational, social animal. Wolfe writes —

...the question “What is man?” is not answered fully with a description of his rationality or highest faculties. ...we are social creatures. ...Since man cannot achieve his earthly and heavenly ends when solitary, man congregates (by instinct and reason) into familial, social, and political groups for mutual support, cooperation, and protection.11

From this stated anthropology, it follows that the natural state of man is one of complete inter-dependence. This axiomatically rules out rational and moral autonomy, for the individual is brought into existence by, and can only come to completion through, the social body. To put the matter concisely: Wolfe’s anthropology, and consequently his view of society, is collectivistic.

This, however, is obscured by Wolfe’s spurious distinction between “unhealthy individualism” and “healthy individualism,” and his criticism of Christians who stand in opposition to individualism. Wolfe writes —

The Christian trend of attacking “individualism” is a mistake. There is certainly an unhealthy individualism, either the fake expressivist variety or the libertarian version that denies pre-political ties and unchosen bonds. But healthy individualism expands each person’s possibilities for action and development.12

While it may appear to some that Wolfe is affirming a different kind of individualism, that is not the case. The careful reader will note that Wolfe’s assertions implicitly affirm Trueman’s Hegelian critique of modernity and the “modern” self, going so far as to lump so-called “expressive individualism” together with libertarian individualism. What is more, for Wolfe “healthy individualism” holds to a view of the individual as interdependent on the social body for his existence and the expansion of his “possibilities for action and development” aimed at the common/communal good. Thus for Wolfe, “the true return to American individualism will require local networks of counter-economies in which each family can aid others with practical skills for necessary goods.”13 This is not individualism at all; it is collectivism.

Strictly speaking, the technical term for what Wolfe is describing is communitarianism, a philosophy that teaches “human identities are largely shaped by different kinds of constitutive communities (or social relations) and ...human nature...inform[s] our moral and political judgments as well as policies and institutions.”14 Like Wolfe,

Communitarians believe that individuals fulfill themselves and contribute to society through participation in a single overarching community as well as through their participation in specific community groups organized on the basis of such common characteristics as geography, gender, race, ethnic background, economic interest, professional interest and cultural interest.15

Individuals, in other words, come to be through, and fully develop only by means of, the social body. Communitiarians also, like Wolfe, argue that

Healthy communities encourage individual self-development and at the same time command centripetal forces that seek to pull in members’ commitments, energies, time and resources for what the community as a collectivity endorses as its notion of the common good.16

In this situation, the collective takes precedence over the individual. Wolfe’s communitarian outlook, in which “the good of one cannot be separated from the good of all,”17 is built on Thomas’ thinking, and resonates with the communitarian teaching of Rerum Novarum and Centesimus Annus,18 and can be traced back even further in papal encyclicals to at least 1740.19

However, in addition to Thomism, Wolfe also pulls from the counter-enlightenment philosophies of G.W.F. Hegel and Johann Gottfried Van Herder. John D. Wilsey notes that “throughout [The Case for Christian Nationalism], Wolfe conceives of the Christian nation in Hegelian terms.”20 His model, argues Wilsey, “bears the substance of Hegel’s statism,” in that it underscores “the nature of the nation-state as totalizing and defined by active will.”21 Additionally, Wolfe’s theory aligns with Hegel’s thinking as regards the magistrate and Christian Prince as having the capacity, right, and responsibility to determine “the appropriate public action for the common good,”22 as they have “the whole in view,” where as individuals and non-magistrates do not.

The philosophy of Johann Gottfried Van Herder, the pantheistic23 counter-enlightenment thinker whom Wolfe falsely identifies as a “Christian philosopher,”24 also surfaces in The Case for Christian Nationalism. Herder’s understanding of the individual as the product of dialogical interactions mediated by social institutions has influenced much of the contemporary cultural, moral, and epistemological relativism developed by postmodernist philosophers. As Michael Forster explains —

[Herder believed that]...linguistic meaning is fundamentally social—so that thought and other aspects of human mental life..., and therefore even the very self (since the self is essentially dependent on thought and other aspects of human mental life, and moreover defined in its specific identity by theirs) are so too. ...[Herder’s view] has since fathered a long tradition of attempts to generate more ambitious cases for stronger versions of the claim that meaning—and hence also thought, human mental life more generally, and the very self—is at bottom socially constituted...25

Herder’s reflections on language play an important role, but one that is secondary to the emphasis he places on “embeddedness, horizon, [and] the usefulness of prejudice.”26

This is because Herder “sharply rejects the Cartesian idea of the mind’s self-transparency” and instead insists “that much of what occurs in the mind is unconscious,”27 a view also shared by Wolfe. Like Herder, the postmodernists, and critical theorists, Wolfe places a great deal of emphasis on the priority of “pre-reflective,” “instinctual,” “pre-propositional” experiences over and against reflective, rational, propositional political creeds. He writes —

Our sense of familiarity with a particular place and the people in it—the sense of we—is rooted not in abstractions or judicial norms (e.g., equal protection) or truth-statements. Rather, the nation is rooted in a pre-reflective, pre-propositional love for one’s own, generated from intergenerational affections, daily life, and productive activity that link a society of dead, living, and unborn. ...Political creeds are ancillary or supplemental, but not fundamental.28

Strictly speaking, what Wolfe is articulating here is called phenomenology, the philosophical study of the “appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, [and] thus the meanings things have in our experience.”29 Wolfe, in part, gets these ideas from Herder, whose writings influenced Hegel’s later development of phenomenology. Wolfe also derives them from the phenomenologist philosopher Gaston Bachelard,30 whose book The Poetics of Space played a key role in shaping the postmodern epistemology of proto-Queer Theorist, Michel Foucault.31

The phenomenology articulated by Herder, Hegel, Bachelard, Foucault and other critical theorists is tied to Wolfe’s theory of Christian Nationalism by means of their overlapping concepts of “lived experience.” Promise Frank Ejiofor explains the significance of the concept of “lived experience” for critical theorists. He writes —

...lived experience [in critical theory] derives from the early twentieth-century phenomenological movement...They emphasised interior consciousness of oneself and the world around one: reflection on everyday experiences was considered the true source of knowledge. Concepts such as lifeworld, intentionality, intuition, empathy and intersubjectivity dominated the lexicon of phenomenologists. Over time...the phenomenological worldview was surreptitiously adopted by sociologists. ...[who] came to see the lived experiences of their research participants as scientific―objective―knowledge, which could be tailored to addressing practical social conundrums including racial discrimination, gender inequality, urban segregation, crime and deviance.32

Identity politics relies heavily on this notion, viewing “lived experience as all there is to knowledge, as unique to specific groups and as something that cannot be understood, critiqued or assessed by people from outside those groups.”33 For a political theory that is supposed to combat the critical identity politics movements destroying the West, Wolfe’s Christian Nationalism depends on some of the same sources and key ideas which are central to critical theory.

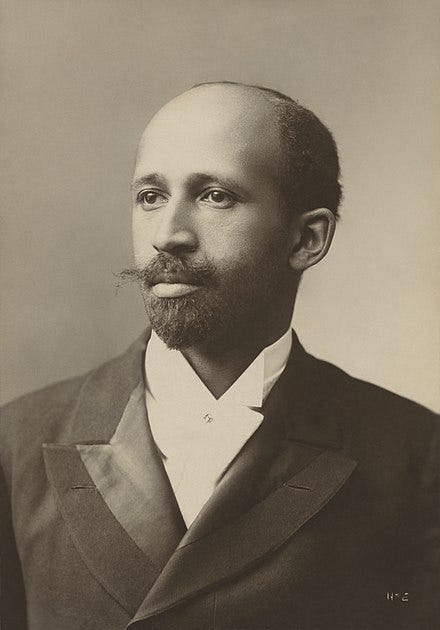

While we have mentioned the relationship of Herder to Queer Theory by way of phenomenology, we can also link Herder’s thinking to Critical Race Theory. For as Sonia S. Lee explains, it was Herder who “first introduced [W.E.B] Du Bois to the romantic conception of each nation having a distinct spirit, a Volksgeist (a ‘national soul’),” from whom Du Bois “...selectively drew upon...intellectual tools...to conceptualize the black “soul” as both a nationalist and cosmopolitan identity,” and whose “...conceptualization of the Volksgeist fundamentally shaped Du Bois’s proposal to advance the “growth and development of the Negro” in his publication, ‘Conservation of the Races’ (1897).”34 Without Herder’s counter-enlightenment philosophy, there would be no Critical Race Theory.

As we have seen, the overlap between Wolfe’s sources and ideas with those of the critical theorists is not merely linguistic; it is substantial. They share the same sources, and develop the same ideas, albeit in somewhat different directions. What Wolfe’s Thomistic Romanticism is not a corrective to critical identity politics, but a perpetuation of it under a different name, and through a different set of exoteric doctrines. And the same must be said of Doug Wilson’s thinking, to which we turn next.

III. Pushing the Synthesis

According to Doug Wilson, “the antithesis between good and evil extends into everything,”35 such that if we do not “begin with the antithesis, we will soon belong to the devil’s party.”36 This is not merely related to morality, but, as he explains, epistemology as well.37 Thus, it also affects one’s beliefs regarding anthropology and politics, and one’s analysis of what is wrong with one’s culture. The point of irony here is that Wilson’s criticism of “modernity” is identical to that which we have traced back to the counter-enlightenment philosophers, as are his anthropology and political thinking. That is to say, Wilson believes that “modernity” is too individualistic, that man is inter-dependent as opposed to independent, and that a communitarian political solution to these problems is ideal. Seeing as these ideas have been derived from non-Christian and anti-Christian sources, Wilson is not pushing the antithesis between Christian and non-Christian philosophies; he is pushing the Thomistic Romanticism synthesis mentioned above.

Regarding the modern era, Wilson argues that we are living in “a generation chock-full of individualism and me-first-ism,”38 and identifies postmodernism, which is clearly tied to moral relativism and degradation, as individualistic in nature,39 though, in reality, it clearly is not.40 According to Wilson we are “in the grip of radical individualism”41 to such an extent that we overlook someone else’s violation of God’s Law if we believe they are simply expressing their point of view. Indeed, part of the “Politics of Sodomy,” according to Wilson, is an individualism, in which he includes American individualism, that rejects Christ’s Lordship over all areas of life.42 Individualism has affected all of the West negatively, including churches in the West. For Wilson, “individualism laid waste to the only environment within which individuals can thrive,”43 as it is the source of relativism,44 and significantly contributes to the State’s metastasization.45 To put the matter succinctly, Wilson believes that “the modern temptation to individualism is a far cry from being a libertarian answer to collectivism, and is rather one of the central reasons why collectivism has swallowed up so much.”46

The true solution to our age’s rampant problem of individualism is, Wilson argues, a proper anthropology in which we recognize that “we are not individuals...[but]...interdividuals.”47 Wilson’s “intervidual” is a clumsy neologism intended to communicate that man is essentially interdependent. As an interdependent being, he must, consequently, engage with others in a communitarian manner. This is a point Wilson makes numerous times. For instance, in his article “Little Platoons,” he writes —

Individuals are in no position effectively to resist the encroachments of the state. For that we need Edmund Burke’s little platoons. Subordinate loyalties give society a molecular rigidity and structure. This means there must be a profound commitment to the covenant of marriage, a real hostility to divorce, a true dedication to bringing up the kids in the nurture and admonition of the Lord, and so on.48

These “little platoons” are little collectives, social bodies that comprise the larger social body. This is, once again, a form of communitarianism. It is, Wilson believes, the only way that Christians can combat the cultural degeneration taking place before our eyes. He writes —

...the only true and effective resistance to the grasping attempts of our jitney overlords is going to come from the molecular bonds found in multiple loyalties, and cannot arise from atomistic individualism. It is also a concern because ultimately libertarian individualism will be ineffective against the demands of the collective. The demands of the swollen state must be answered by interlocking and rightly proportioned societies. We need principled Christian resistance, and we need it in the worst way. But principled Christian resistance will have to be based on Burkean localism, and not based on a libertarian individualism.49

The underlying ideas here are identical to what we have seen in Wolfe — atomistic individualism is the cause of society’s collapse, it is ineffective against big government, it contributes to the endless growth of the State, it contradicts human nature seeing as we are essentially interdependent, and, therefore, should be replaced by a well-formed state that will reflect that interdependence — a form of “Burkean” localism (i.e. communitariansim) — and, thereby, provide real opposition to “our jitney overlords.”

The similarities between Wilson the Wolfe extend beyond their shared opposition to individualism and promotion of communitarianism, to a view of language as inherently anti-individualistic.50 Yes Wilson, like Wolfe, Herder, Hegel, the postmodernists, and critical identity theorists, believes that language in se is evidence against the idea of rational and moral autonomy. This is due to their shared dependence on the same sources for the same ideas. Wolfe’s dependence on Herder’s counter-enlightenment/romanticist philosophy is paralleled by Wilson’s dependence on Edmund Burke’s, a thinker whose ideas have so influenced Wilson’s political theorizing that he calls himself a “Burkean conservative.”51 This is significant, for as Zeev Sternhell explains,

...in terms of a direct and immediate influence, the founders of Anti-Enlightenment thought were Johann Gottfried Herder and Edmund Burke.

[…]

Burke and Johann Gottfried Herder, and before them Vico, had launched a campaign against the French Enlightenment, rationalism, René Descartes, and Rousseau long before the storming of the Bastille. ...Burke made his first criticisms forty years before the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and Herder, who, despite his opposition to the French Enlightenment, enthusiastically welcomed the fall of the authoritarian monarchy in France, demonstrated his hostility to the principles represented by the philosophes from 1769 onward.52

[...]

With the exception of Herder, no critic of the Enlightenment before Burke had attacked the very foundations of Enlightenment thought with such virulence. Contrary to a common idea largely accepted today, the importance of Edmund Burke was not that he was a pillar of the English liberal tradition but that, together with Herder, he was one of the two great founders of a new political tradition, that of a different modernity based on the primacy of the community and the subordination of the individual to the collectivity. ...Burke’s concept of the political ideal in fact rejected the conception of the autonomy of man, and liberty was reduced to inherited privileges consecrated by usage.53

In addition to Burke, moreover, Wilson also relies heavily on the counter-enlightenment/romanticist thinking of R.L. Dabney54 and Abraham Kuyper, whose Thomistic Romanticism and links to postmodernism have been discussed elsewhere.55 Wilson, in other words, like Wolfe is pushing the synthesis — Thomistic Romanticism — and leading Protestants toward Roman Catholic Integralism.

See Diaz, Hiram. “You Can’t Fight Hegel With Hegel”, Sovereign Nations, April 26, 2023, https://sovereignnations.com/2023/04/26/cant-fight-hegel-with-hegel/.

See Diaz, Hiram. “The Myth of Excessive Individualism & The Road to Christian Nationalism”, Sovereign Nations, May 4, 2023, https://sovereignnations.com/2023/05/04/myth-of-excessive-individualism-to-christian-nationalism/; Praamsma, Louis. Let Christ Be King: Reflections on the Life and Times of Abraham Kuyper (Ontario: Paideia Press, 1985), 7-12.

The Revival of Scholastic Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century, Jacques Maritain Center, https://maritain.nd.edu/jmc/etext/perrier1.html.

See Ferrarin, Alfredo. Hegel and Aristotle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), “Aristotelian and Newtonian Models in Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature”, 201-233.

See Schloesser, Stephen. “Passion of Israel: Jacques Maritain, Catholic Conscience and the Holocaust (review)” in Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, Vol. 29, No. 4 (2011), 193-196.

See Bauer, Michael. “Hegel and Aquinas on Self-Knowledge and Historicity”, in Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, Vol. 68 (1994), 125-134.

Shortall, Sarah. Soldiers of God In A Secular World: Catholic Theology and Twentieth-Century French Politics (Cambrdige: Harvard University Press, 2021), 10.

See Peterson, Paul Silas. The Early Hans Urs von Balthasar: Historical Contexts and Intellectual Formation (Munich: de Gruyter, 2015).

See Kristiansen, Ståle Johannes. “Pave Frans’ Forhold til Katolsk Kontinental Teologi (Pope Francis and Catholic Continental Theology)”, in Årgang Vol. 9, No. 4 (2020), 230–244.

Wolfe does not argue for this anthropology from Scripture, but explicitly states that he is dependent on those who have accepted it within the Reformed tradition. Early on in The Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow: Canon Press, 2022), Wolfe writes —

...I pull mainly from the 16th and 17th centuries, in which Reformed theology was very Thomistic and catholic...

—[Kindle loc. 227]

Explaining,

By “Thomistic,” I mean that Reformed theologians in these centuries were heavily influenced by Thomas Aquinas.

—[Kindle loc. 549]

ibid., Kindle loc. 574-580. (emphasis added)

The Case for Christian Nationalism, Kindle loc. 6998-7005.

ibid., Kindle loc. 7020-7026. (emphasis added)

“Communitarianism”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, May 15, 2020, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/communitarianism/.

“Communitarian Economics”, in The Journal of Socio-Economics Vol. 26, No. 1 (1997), Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A77876998/AONE?u=googlescholar&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=4e7391aa.

ibid.

The Case for Christian Nationalism, Kindle loc. 2322. (emphasis added)

For more on this, see Williams, Oliver F. “Catholic Social Teaching: A Communitarian Democratic Capitalism for The New World Order”, in Catholic Social Thought and the New World Order: Building on One Hundred Years, Ed. Olive F. Williams & John W. Houck, (Nortre Dame: University of Nortre Dame Press, 1993), 5-28.

For more on this, see Schuck, Micahel J. That They Be One: The Social Teaching of The Papal Encyclicals 1740-1985 (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1991).

“The Christian Prince Against the Dad Bod: An Assessment of The Case for Christian Nationalism”, The London Lyceum, April 28. 2023, https://www.thelondonlyceum.com/book-review-the-case-for-christian-nationalism-stephen-wolfe/.

ibid.

ibid.

See Beiser, Frederick. “Herder, Johann Gottfried (1744–1803)”, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/biographical/herder-johann-gottfried-1744-1803/v-1/sections/philosophy-of-mind-2.

The Case for Christian Nationalism, Kindle loc. 2137-2145.

“Johann Gottfried von Herder”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, May 19, 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/herder/.

ibid.

ibid. (emphasis added)

The Case for Christian Nationalism, Kindle loc. 1902-1909. (emphasis added)

Smith, David Woodruff. “Phenomenology”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Dec. 13, 2016, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/.

Wolfe’s section on Time and Intergenerational Love elaborates on the significance of household objects of experience (Kindle loc. 2013-2019), referencing Gaston Bachelard’s work The Poetics of Space in footnote 11 (Kindle loc. 2579).

See Simons, Massimiliano, et al. “Gaston Bachelard and Contemporary Philosophy”, in Parrhesia Vol. 31 (2019), 1-16.

“The Limits of Lived Experience”, Aero, April 2, 2021, https://areomagazine.com/2021/02/04/the-limits-of-lived-experience/. (emphasis added)

ibid.

“The Uncertain Power of Blackness: A philosopher meditates on Du Bois’s double consciousness”, The Common Reader: A Journal of the Essay, Feb. 29, 2016, https://commonreader.wustl.edu/c/4257/.

“Divided Loyalties”, Blog & Mablog, May 2, 2004, https://dougwils.com/the-church/sacraments/divided-loyalties.html.

“Blessednesses/Psalm 1”, Blog & Mablog, April 26, 2004, https://dougwils.com/the-church/s8-expository/blessednesses.html.

“The Devil’s Dictionary”, Blog & Mablog, Jan 21, 2005, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/books/the-devils-dictionary.html.

“Four Questions for Christian Libertarians”, Blog & Mablog, Sept 18, 2020, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/four-questions-for-christian-libertarians.html.

See “Got My Pomojo Working”, Blog & Mablog, Sept 5, 2006, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s21-atheism-and-apologetics/got-my-pomojo-working.html.

See Diaz, Hiram R. “Postmodernism is Not Individualistic: A Brief Correction to a Popular Error”, Logia, April 19, 2023, https://logia.substack.com/p/postmodernism-is-not-individualistic.

“Trial By Internet”, Blog & Mablog, March 10, 2006, https://dougwils.com/books/trial-by-internet.html.

See “The Politics of Sodomy”, Blog & Mablog, June 29, 2006, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/the-politics-of-sodomy.html.

“Liberty Redefined”, Blog & Mablog, March 15, 2021, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/liberty-redefined.html.

See “Introduction to Truth”, Blog & Mablog, Feb 22, 2021, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/the-coming-collapse-of-secular-man.html.

See “That Cut Flowers Kind of Religious Liberty”, Blog & Mablog, June 24, 2019, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/that-cut-flowers-kind-of-religious-liberty.html.

“Little Platoons”, Blog and Mablog, Oct 7, 2020, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/how-hospitality-weaves.html.

“Gladness and Strength”, Blog and Mablog, June 25, 2006, https://dougwils.com/books/gladness-and-strength.html.

ibid. (emphasis added)

“Public Health and the Libertarian Lure”, Blog and Mablog, Oct 18, 2021, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/public-health-and-the-libertarian-lure.html. (emphasis added)

See “What Do You Mean By ‘Fish’?”, May 29, 2006, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/books/what-do-you-mean-by-fish.html.

“My Part in a Delightful Little Proxy Row”, Blog & Mablog, Nov 28, 2022, https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/my-part-in-a-delightful-little-proxy-war.html.

The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 2-4. (emphasis added)

ibid., 59-60. (emphasis added)

Dabney’s counter-enlightenment epistemology, central to his refutation of moral relativism, is similar to what we find in Wolfe’s Herderian phenomenology, and Romanticism as a whole. For more on this, see McPherson, Robert J. “Dabney’s Refutation of Relativism”, https://thereformedconservative.org/dabneys-refutation-relativism/. Dabney’s communitarianism has been well noted by several scholars. For more on this, see Farmer, James Oscar. The Metaphysical Confederacy: James Henley Thornwell and the Synthesis of Southern Values (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1986); Schlebusch, Jan Adriaan. “The Role of Familialism in Counter-Enlightenment Social Ontology”, in Journal for Christian Scholarship Vol. 57, No. 3-4 (2022); and Harp, Gillis J. “Traditionalist Dissent: The Reorientation of American Conservatism, 1865-1900”, in Modern Intellectual History Vol. 5, Iss. 3 (2008), 487-518.

See Diaz, Hiram. “PoMo and Presup: Explaining their Relation”, Logia, July 30, 2023 —

PoMo and Presup

Van Til, Kuyper, and Organicism Years ago, I encountered a critic of Van Tillian presuppositionalism who argued that presuppositionalism is more or less a Christianized form of postmodernism. I was never a Van Tillian, but I did appreciate the work of some of his acolytes, and so the claim bothered me. How could presuppositionalism be related to postmode…